The AI's Capex Trap

Why the biggest technology boom in history is also the most fragile capital structure ever built, and why it might be good for India

Some folks, in US believe,

In World War II, America did not win because it had better pilots or smarter generals. It won because it built more stuff than everyone else combined.

The U.S. produced roughly 300,000 aircraft and 61,000 tanks in a few years — more than Germany and Japan together could hope to match. The Axis could still design brilliant weapons. They could still fight ferociously. But industrial scale turned warfare into an arithmetic problem. And then came the bomb. The atomic bomb did not win the war by itself. It merely ended it cleanly.

Today, Silicon Valley, and Wall Street are obsessed with AGI, a god-like intelligence, the hypothetical “nuclear weapon” of the digital era.

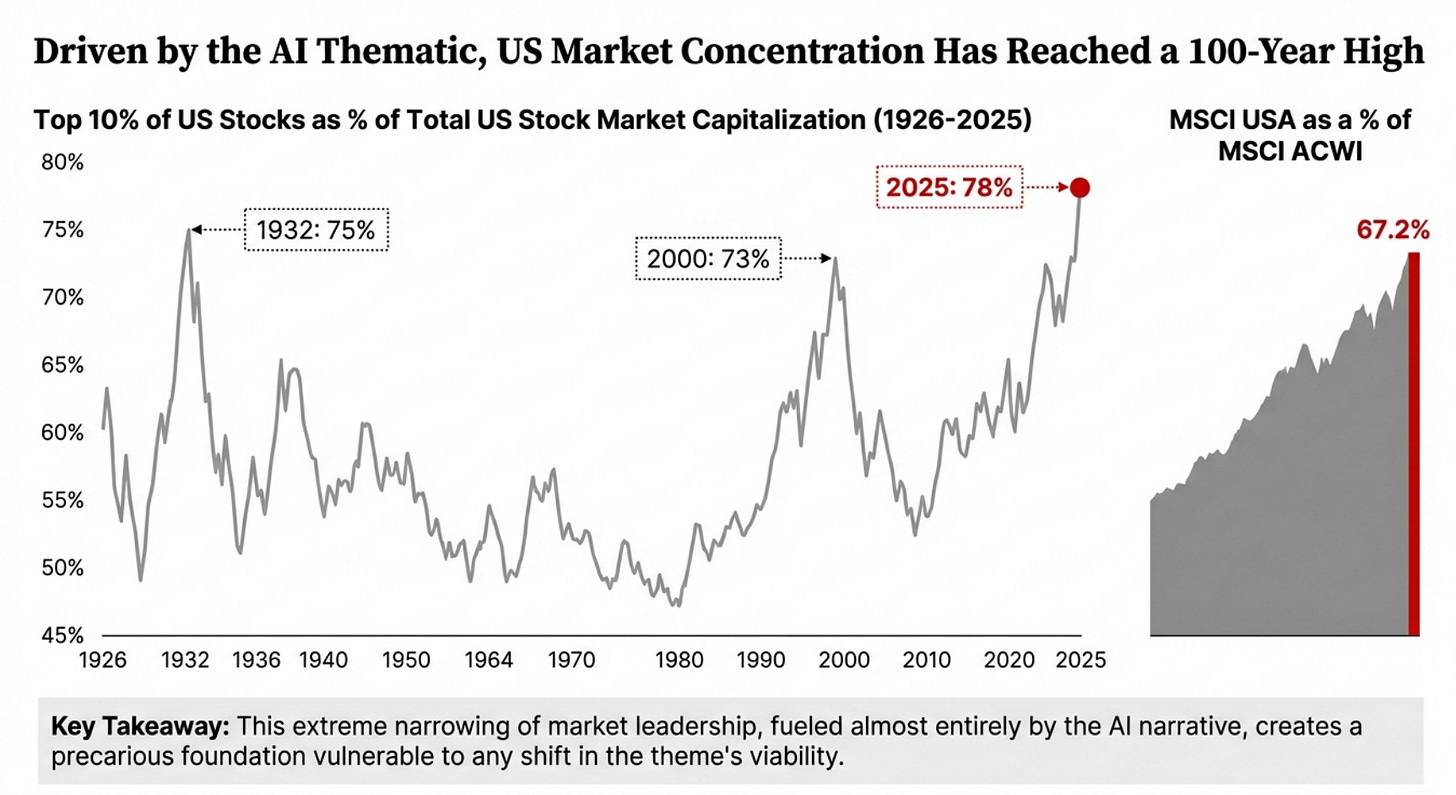

We are told this is a technology cycle. What is happening is a massive capital cycle disguised as technological progress. The scale of the build-out is staggering, the largest fixed-infrastructure deployment since the 1940s.

But instead of concrete and steel, we are pouring money into data centers, trillions in machines designed to churn tokens. Capital cycles are predictable: they end not when the technology fails, but when the cost of sustaining the infrastructure exceeds the revenue generated by it.

On that math, the AI boom is not just the biggest technology story of our lives — it is the most fragile capital structure ever built.

Tokens Without Revenue

I run a two-person company. My partner handles engineering and data. I handle everything else. Our revenue per employee sits in the top half-percentile in India. When people ask why we don’t expand the team, the answer is not strategy. It’s AI.

That is what enterprise AI now looks like at scale.

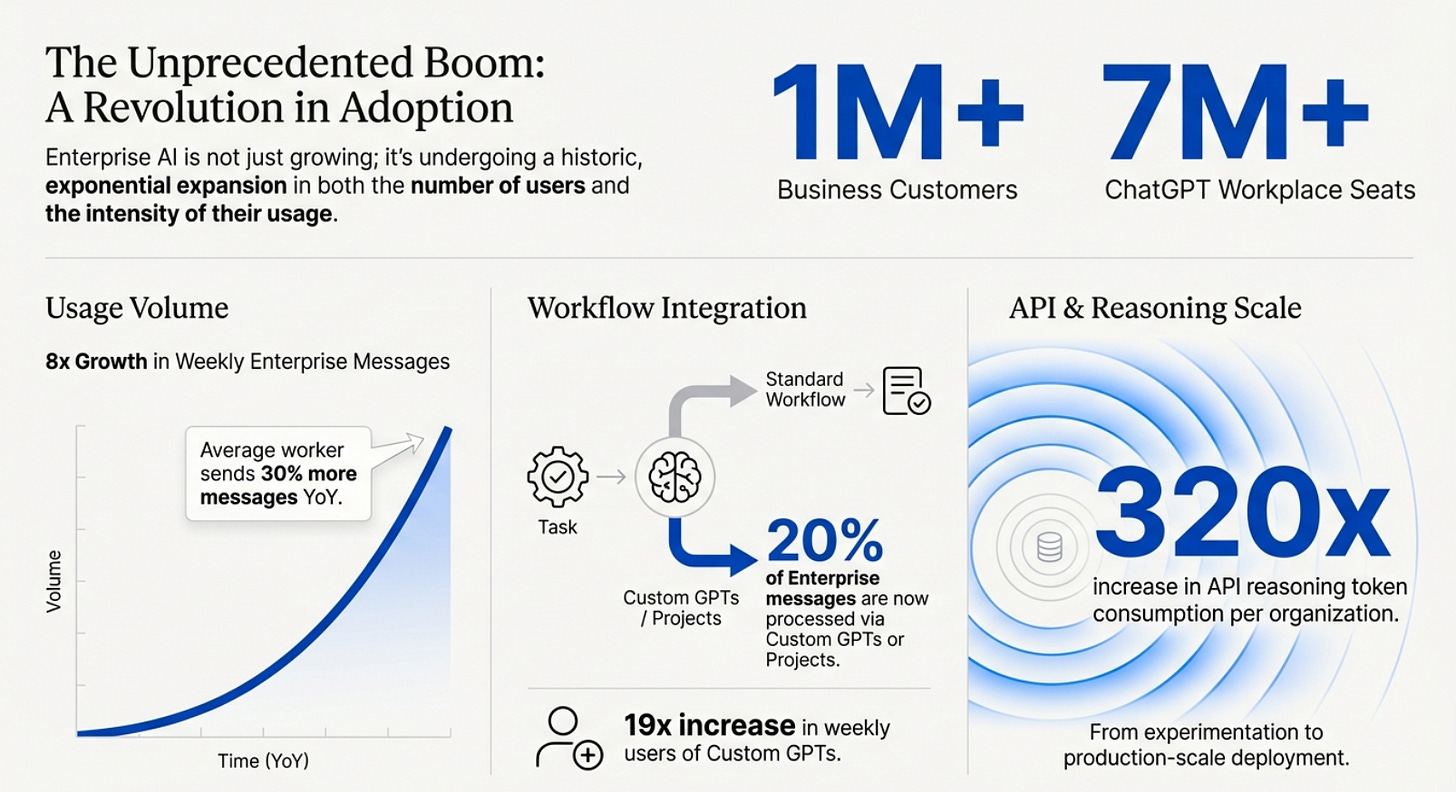

As per the The state of enterprise AI report by OpenAI

Average reasoning token consumption per organization is up 320× in 12 months

9,000+ companies have processed over 10 billion tokens, and 200+ have crossed 1 trillion tokens

75% can now do tasks they couldn’t do before (coding, analysis, automation)

OpenAI, can claim to found their Power Users. And, for them, gains are real.

But they are not the business model.

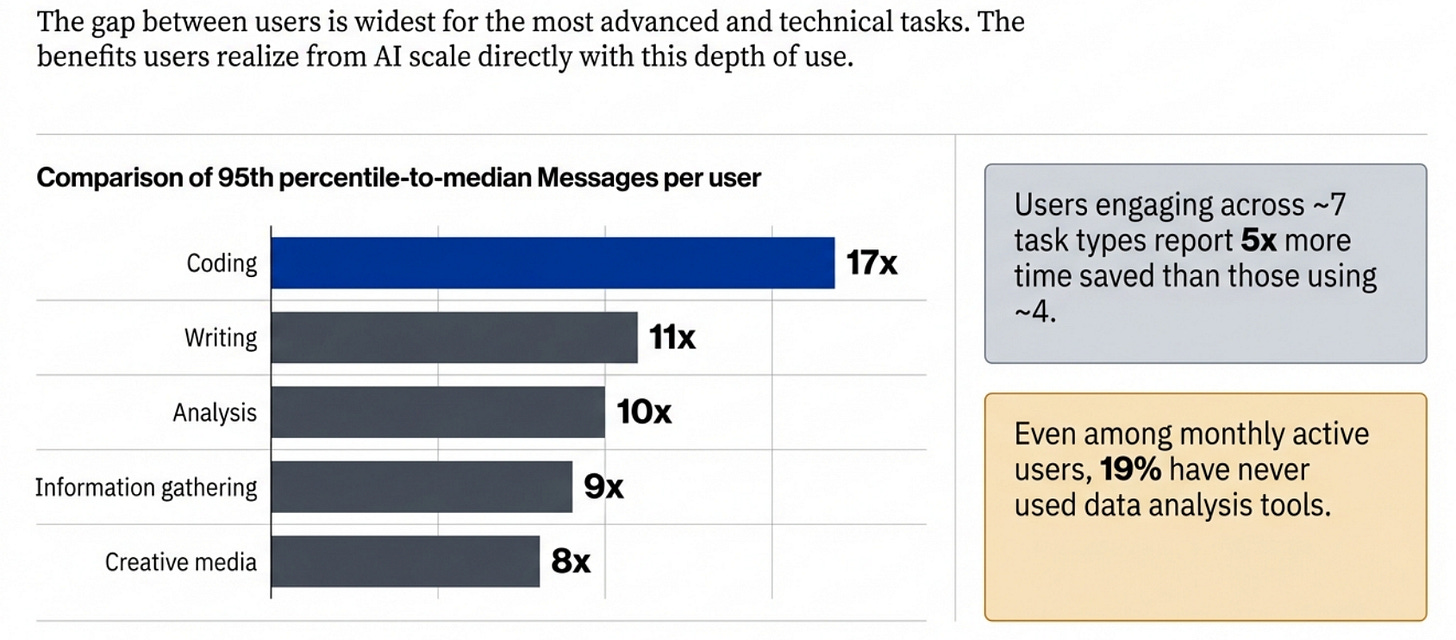

This is the confusion at the heart of the AI boom: productivity is not profit.

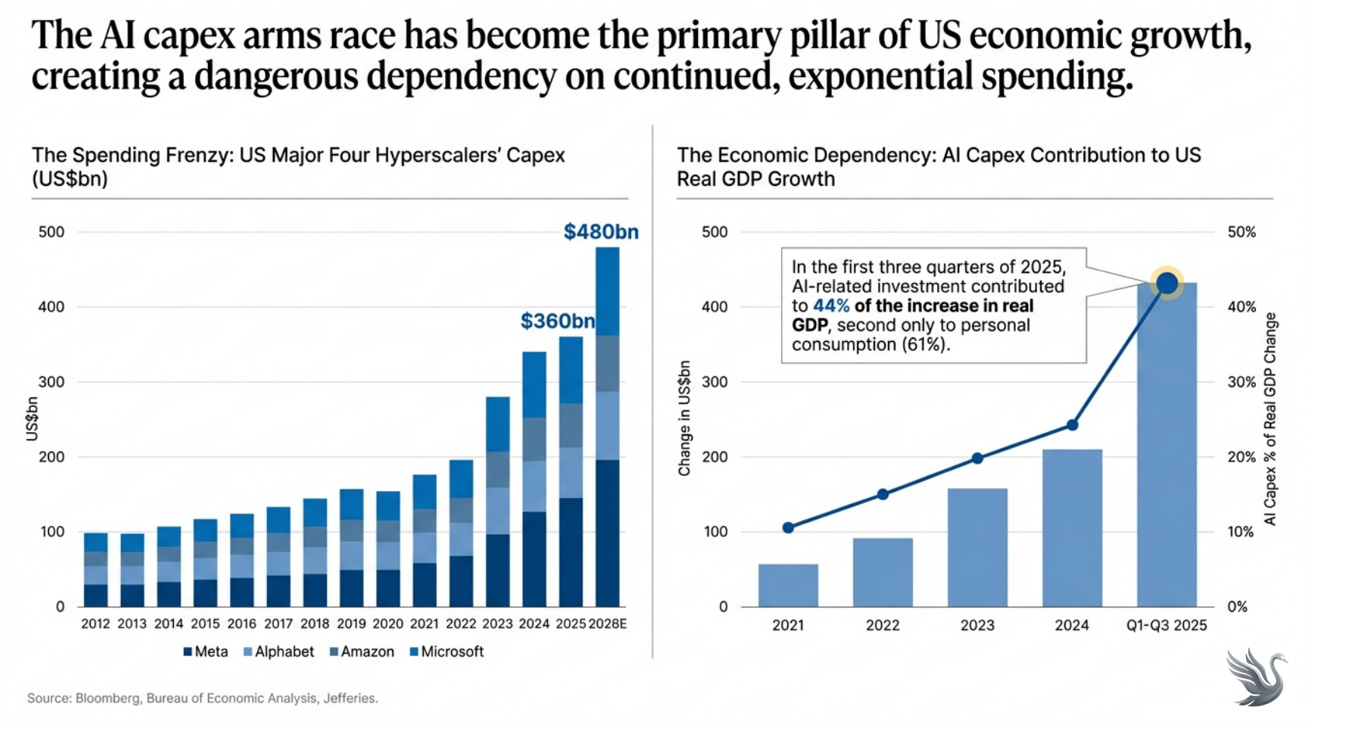

Enterprise AI data now reveals something uncomfortable.

Token consumption is rising hundreds of times faster than revenue ever could. Thousands of companies have already processed tens of billions of tokens. Hundreds have crossed into the trillions. Usage is exploding not in experimentation, but in production.

But pricing does not scale with tokens. Most firms pay flat seat fees or capped enterprise contracts. As employees save more time, they use more AI—but they do not pay proportionally more.

This is the signature of a utility. Demand grows faster than pricing power.

In the SaaS era, software captured the value it created. Customers paid recurring fees for access to tools that locked them in. Unlike the SaaS era where vendors captured value, the economic surplus from AI productivity is diffusing to employers and customers.

In the AI era, the value leaks. If a model makes an analyst 50% more productive, the surplus belongs to the firm that employs the analyst, not to the company that trained the model.

The more essential AI becomes as a general-purpose input, the harder it is to charge monopoly rents. If this remains like this, well then its like building a global cognitive utility, and utilities, for everyone, have never been good businesses.

I know, I am contradicting myself form what I wrote few weeks back at The Efficiency Trap: Why AI Is Not a Productivity Story

The Compute-Driven Economy and the Monetization Abyss

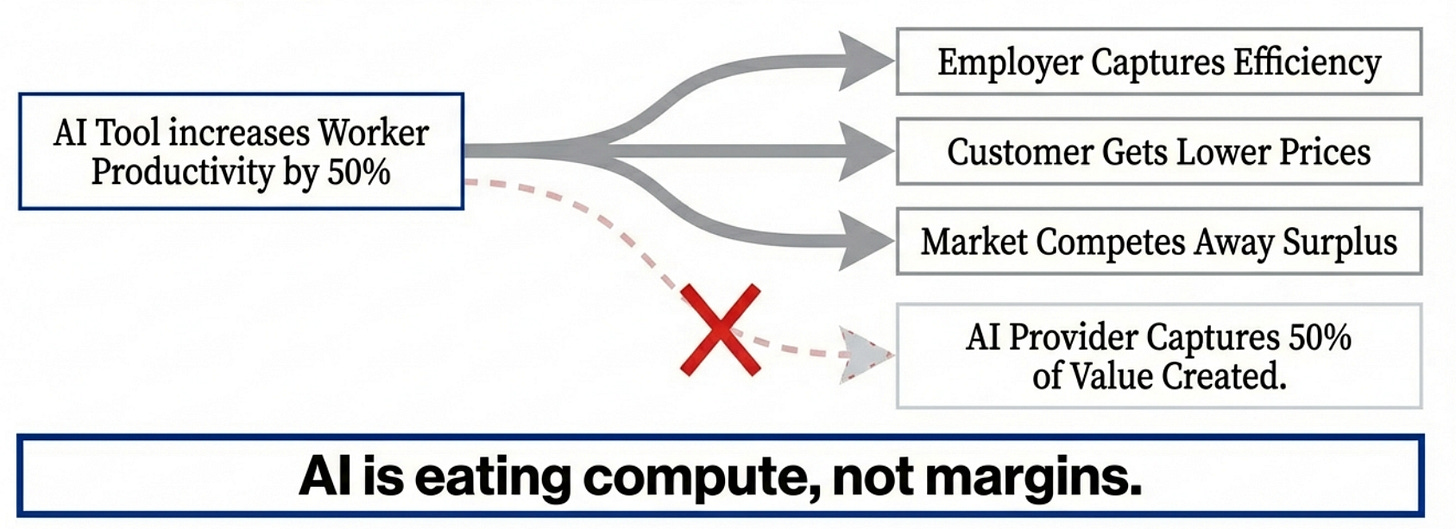

The U.S. economy has quietly changed its engine. It is no longer primarily driven by consumption or services. It is driven by compute.

In the first three quarters of 2025, real GDP in the U.S. rose by roughly $438 billion, and about 44% of that came from AI-related fixed investment — data centers, H100/H200 GPUs, software, and specialized processors. This level of contribution is something normally seen in wartime mobilization or speculative booms.

US is structurally dependent on the build phase of AI. If hyperscalers slow their capital spending, GDP doesn’t just decelerate — it sags. The economy has become reliant on chips and servers being bought at scale, even though the earn phase — actual revenue from AI — has barely begun to exist.

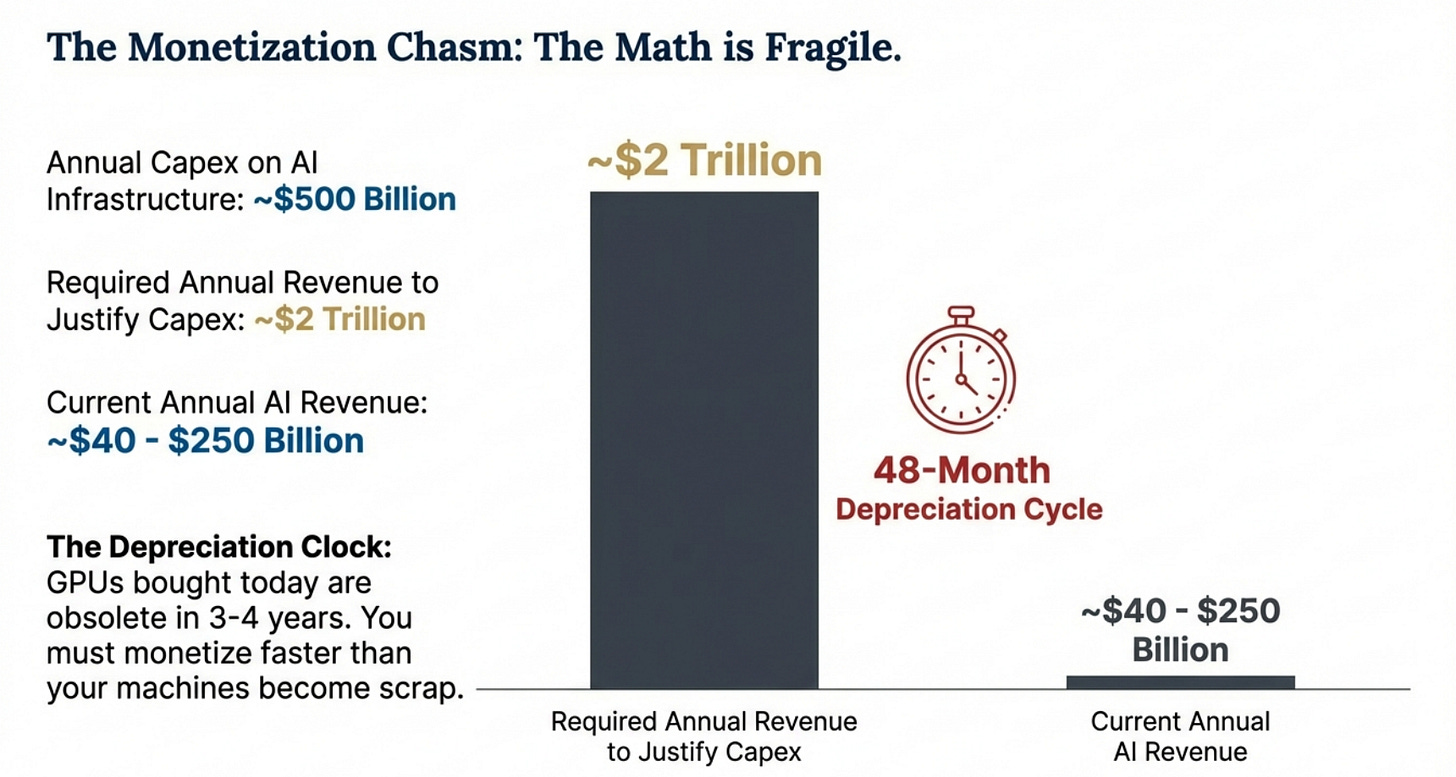

And here is the sharpest contradiction: to justify roughly $500 billion per year of AI infrastructure spending, the industry would have to generate nearly $2 trillion in annual revenue. Current AI-specific revenues are in the tens of billions. This isn’t a gap — it’s an abyss. For today’s valuations to hold, AI revenue would need to grow by eight to fifty times in the next few years — while the hardware being built today depreciates in three to four years.

The hyperscalers are not spending because they see a clear path to that revenue. They are spending because they fear being left behind. FOMO is no longer a cultural trope — it’s a board-level capital policy.

By 2026, capex for these firms is expected to absorb nearly 70% of operating cash flow — numbers more akin to railroads and telecoms in their prime, not tech giants.

The Utilization Wall

This boom is not going to end because AI stops working. It will end because too much capital was deployed into assets that depreciate faster than they can be monetized. Every GPU cluster bought today has a clock on it. Three to four years, and it is no longer competitive. That is not software. That is aviation.

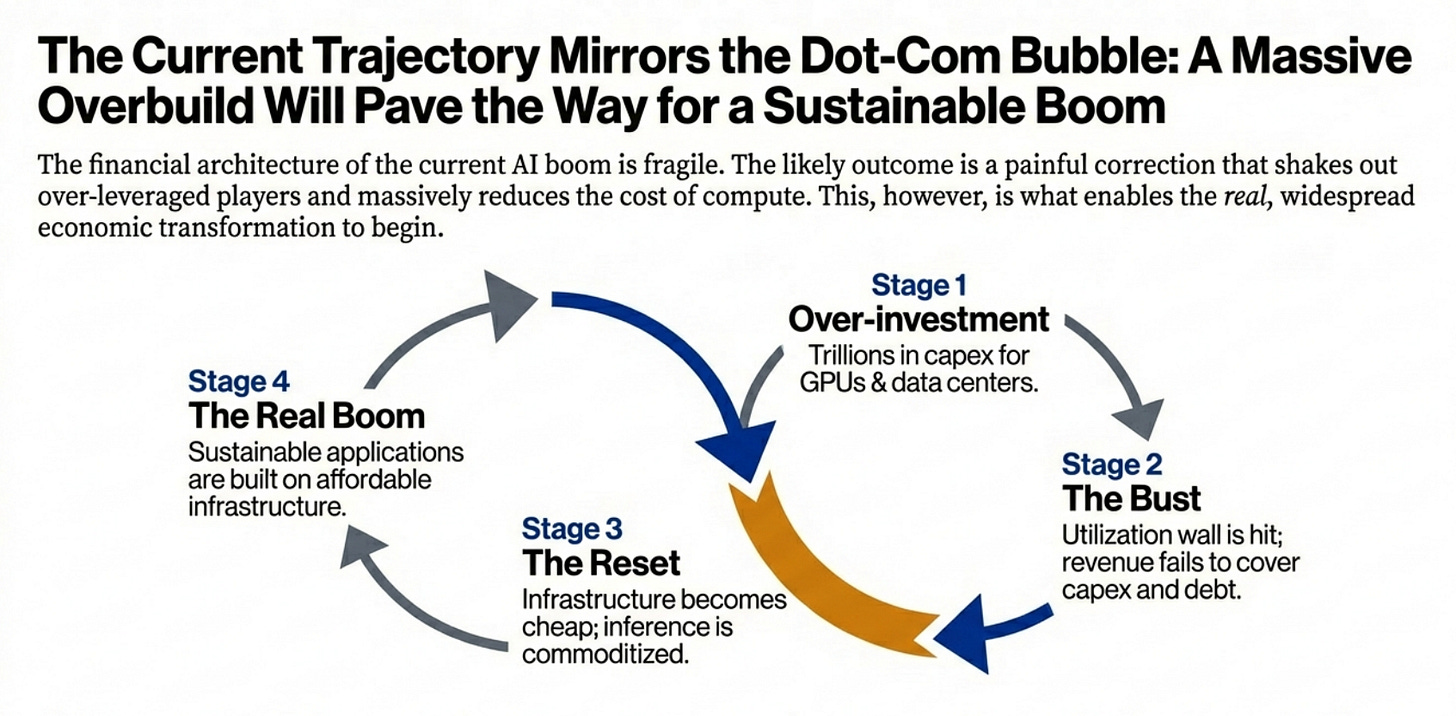

At the same time, the output of these machines — tokens — is becoming interchangeable. Models converge. Open-source spreads. APIs get standardized. When output becomes a commodity and capital keeps piling in, you get one thing: overcapacity.

That is the Utilization Wall. It is the moment when companies realize they have more compute than they can sell at profitable prices.

"The tragedy of the capital cycle is that the early investors lose. Civilization wins."

When that happens, pricing collapses. Assets get written down. Credit tightens. Expansion turns into liquidation.

That is how railroads ended (the original platform play).

That is how telecom ended (the tech as infra).

That is how airlines work (utilities for almost everyone).

AI is headed to the same place because it combines rapid depreciation with commoditized output. You cannot outrun that math.

Where the Surplus Goes

When capital collapses, value does not disappear. It moves.

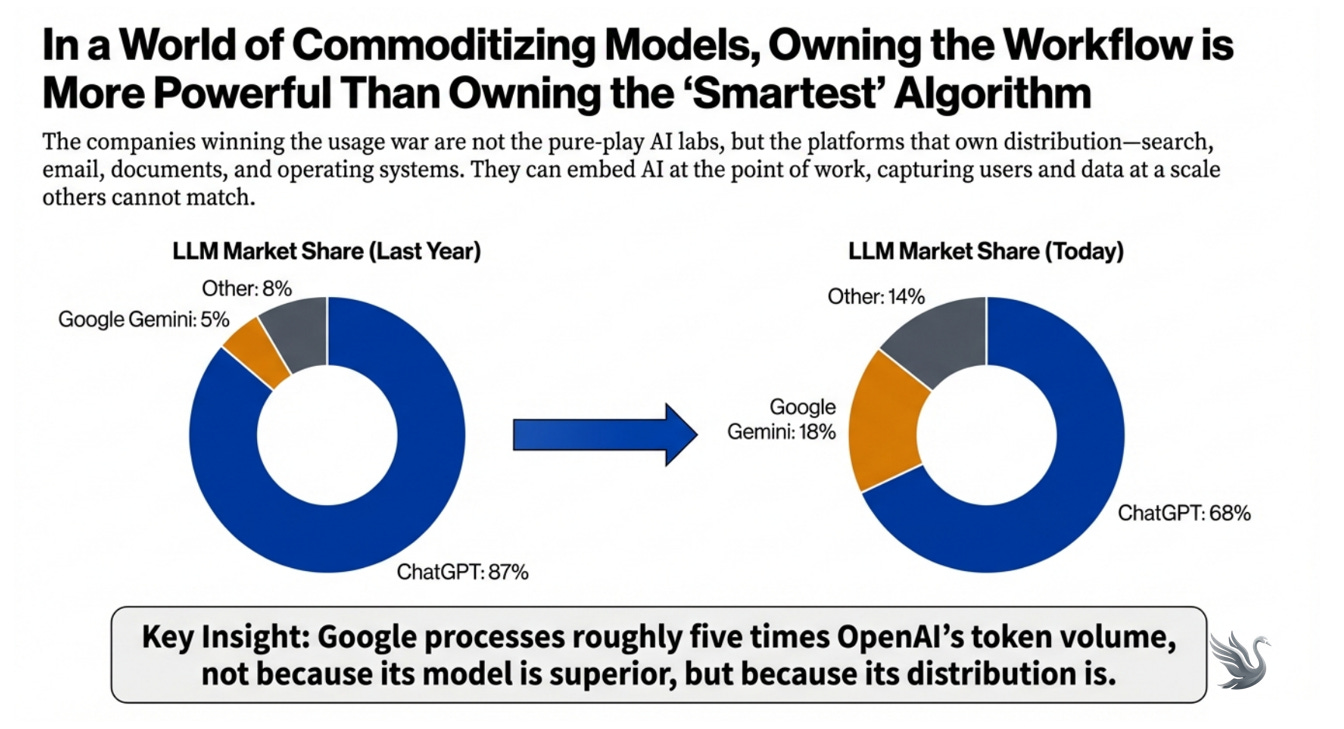

In AI, it moves away from the people who build models and toward the people who control where intelligence is used.

Distribution matters. We are already seeing this with Google. Whoever owns email, search, operating systems, and business software decides which models get traffic. Intelligence flows through pipes, and the pipe owners get paid.

Energy matters even more. Tokens are compute plus power. As models commoditize, the cheapest tokens win. The side that controls electricity, grids, and generation controls the long-run cost of intelligence.

This is why chasing AGI is the wrong frame. AGI is the bomb. But bombs don’t decide economies. Production systems do.

The winners will not be those who create the smartest models.

They will be those who make intelligence cheap, embedded, and unavoidable inside real workflows.

That is where monetization lives.

EndNote: Why This Is Good for India

Distribution, activation, and monetization are not the same war.

Distribution is who owns the user.

Activation is who gets that user to actually work with AI.

Monetization is who captures the surplus that work creates.

Most of today’s AI winners are only winning the first two.

ChatGPT, Claude, Copilot, Gemini — they are training humans to think with machines. That is activation. Google, Microsoft, Apple, and Meta own the screens where that thinking happens. That is distribution. But neither guarantees profit.

When AI helps a company sell more, ship faster, or serve better, the value flows to the company doing the selling, shipping, and serving — not to the model. The model becomes a cost input. It gets negotiated, bundled, and pushed toward zero. This is how utilities are born.

So the real contest is not who builds the smartest model.

The real fight could be: Who owns the workflow where AI creates economic value?

So, it seems Indians have a play here.

India is not strong at building foundation models. India is not strong at Platforms at scale. India is strong at operationalizing complexity at scale. And, India already sells process to the world.

As of now, AI is not platform. They are workflows. And workflows are where monetization happens.

This is why my two-person company works.

We didn’t build the deep-model.

But, we embedded lot of it into how work gets done.

With this, I’m going to pause (again) GreySwan for a few months. I’ll be back in April. By then, the math should be louder than the narratives.

Agree with you. Keep up the good work.

While you are largely correct , the world today is largely disruptive in more ways. Take the case of takeover of venezuela , the whole ball game changed, it is not longer supply-demand theory.so, without considering the elephant in the room , any such predictions are risky. We are not in a perfectly free market with an even playground and common rules.