The Silent Revolution

Why You Are Living an "Extra Life". Why We're Blind to the Progress We Live In?

Gentle readers, let’s start 2026’s first post with an interesting Story.

The Ultimate Grey Swan: Why We Have almost Ignored it.

In the calculus of risk, a “Black Swan” is the outlier that defies prediction. But a Grey Swan is far more insidious: it is the high-impact, high-probability transformation hiding in plain sight, camouflaged by our own cognitive biases or the perceived “boringness” of its structural mechanics.

Human mind is evolutionarily wired to prioritize sudden shocks and acute threats over gradual, compounding progress. So, we often struggle to quantify the slow build because good news is a process, while bad news is an event.

Over the last century, humanity has engineered a feat bordering on the impossible, yet we’ve relegated it to background noise. We fetishize the smartphone, the moon landing, and the trajectory of Large Language Models. We obsess over the volatility of quarterly GDP and the minutiae of productivity curves. Meanwhile, the most radical shift in the human condition—the fact that the average person now lives an entire “extra life” added to the historical species baseline—remains a footnote in our collective consciousness.

This is one of the MOST important achievement in our history, it was/is built incrementally through Sanitation, Modern Medicine, and data (Epidemiology) rather any cinematic “eureka” moments.

Disclaimer: I am writing this, after reading one of my favorite author’s book- EXTRA LIFE, by Steven Johnson, which i recently read.

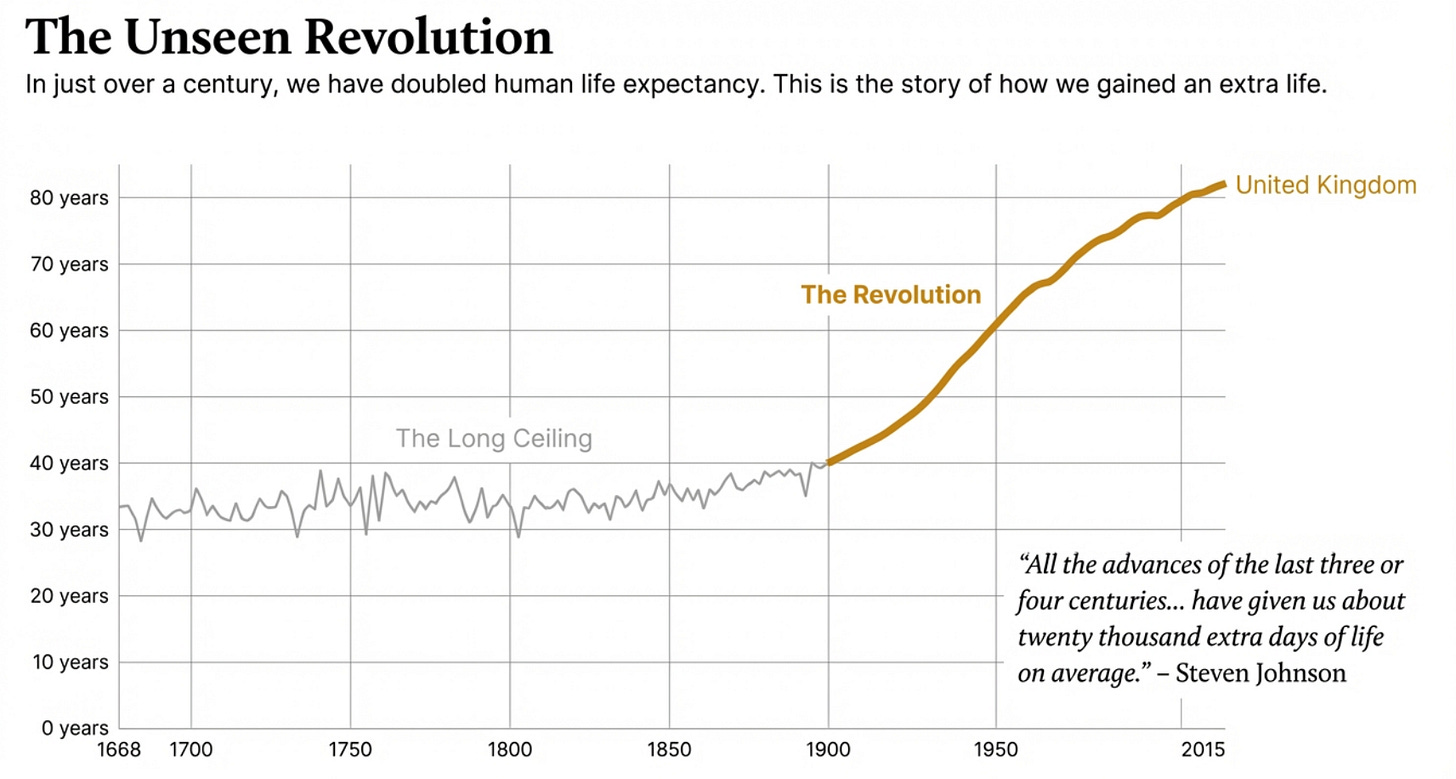

The Long Ceiling: 99% of Our History

For almost all of human history—from Paleolithic hunter-gatherers to the subjects of the Mughal Empire—life expectancy was trapped in a narrow, grim band of thirty to thirty-five years.

This wasn’t a statistical curiosity; it was a structural constraint on the human condition. It didn’t matter if you were a peasant in medieval France or a worker in the early industrial factories of Manchester; the arithmetic of survival remained almost same.

Evolution is not always gradual. It combines long periods of steady refinement with sudden, game-changing leaps.

In classical Hindu thought, aging divides life into stages:

Brahmacharya (learning)

Grihastha (householder)

Vanaprastha (withdrawal)

Sannyasa (renunciation)

Most texts mention each of these as 20 years time band, so Did humans live to 80+ in the past?

Well, this is where intuition breaks. The misunderstanding begins with how we frame longevity. For most of history:

Average life expectancy at birth: 30–40 years

But if someone reached age 20, they often lived into their 70s

Some individuals reached 80s and 90s

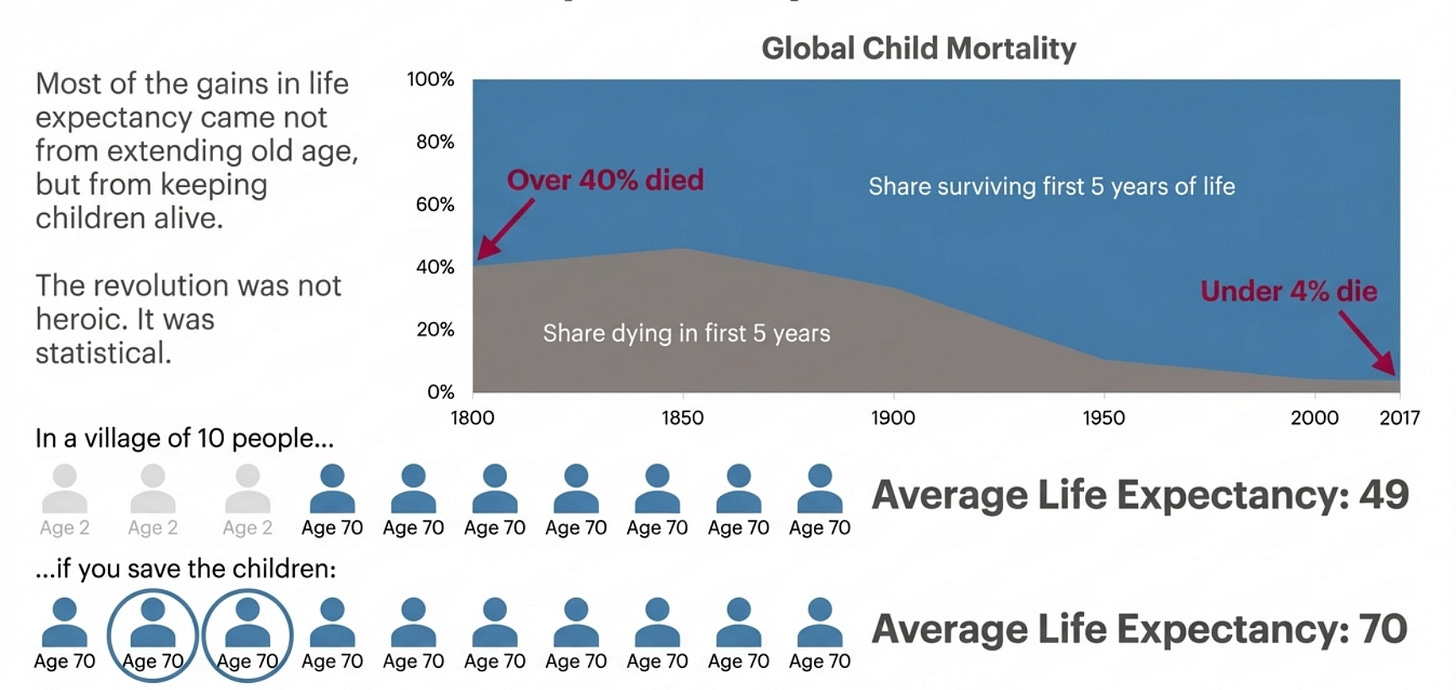

For most of history, childhood was the most dangerous phase of life. In 1800, roughly four out of every ten children globally died before the age of five. Infectious disease, contaminated water, malnutrition, and poor sanitation culled populations relentlessly.

The modern world did not defeat death. It defeated early death.

This distinction matters because it reframes the entire logic of progress. The longevity revolution was not primarily about heroic doctors or miracle drugs. It was about insulation—layer upon layer of protection built between human bodies and the environment.

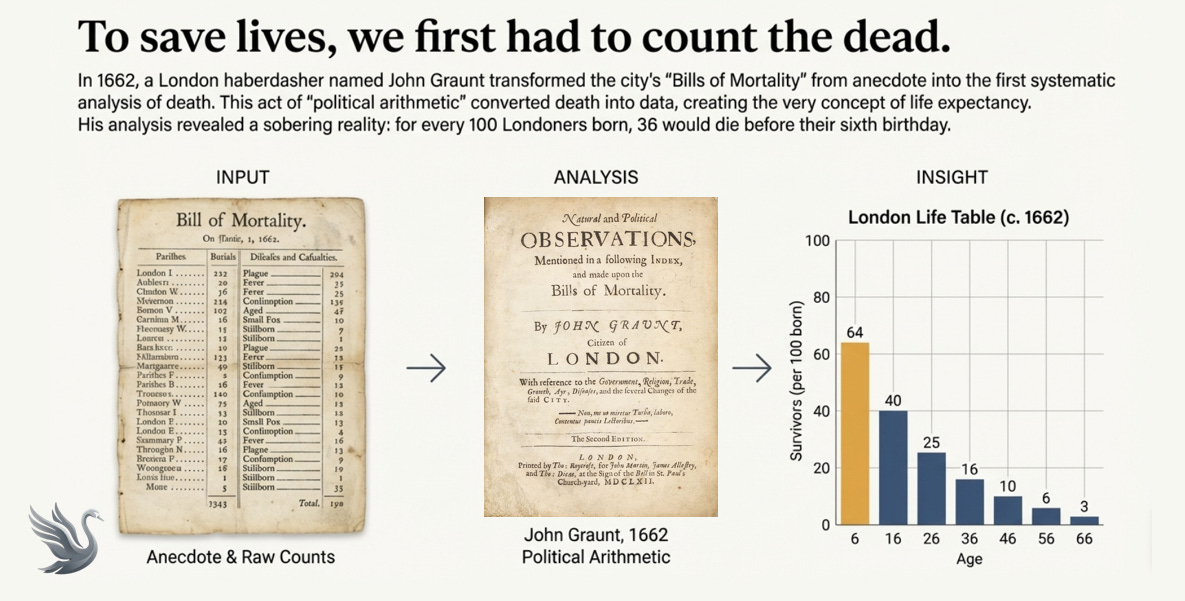

Layer One: The Power of Counting

The first decisive break from the Long Ceiling did not come from a medical cure, but from a counting. Measurement turned death into a solvable problem.

The foundations of modern statistics and demography were laid not by a career academic, but by a London shopkeeper.

John Graunt’s 1662 work, Natural and Political Observations Made upon the Bills of Mortality, transformed simple lists of the dead into a powerful tool for understanding human populations. Graunt saw something deeper in the data: patterns.

The First Life Tables: Graunt created the first “life table,” which estimated the probability of surviving to a certain age. This became the mathematical backbone of the modern insurance and pension industries.

Biological Constants: He discovered that more boys were born than girls, but that men had higher mortality rates, meaning the population eventually balanced out—a ratio that remains a core observation in biology today.

Urban vs. Rural Health: He was the first to provide statistical evidence that people in cities died at higher rates than those in the countryside, despite the “advantages” of urban living.

When deaths began to be recorded systematically, mortality stopped being a moral anecdote and became a measurable phenomenon.

But then, Data is Just a Collection of Facts. Data alone was not enough. It had to be made legible.

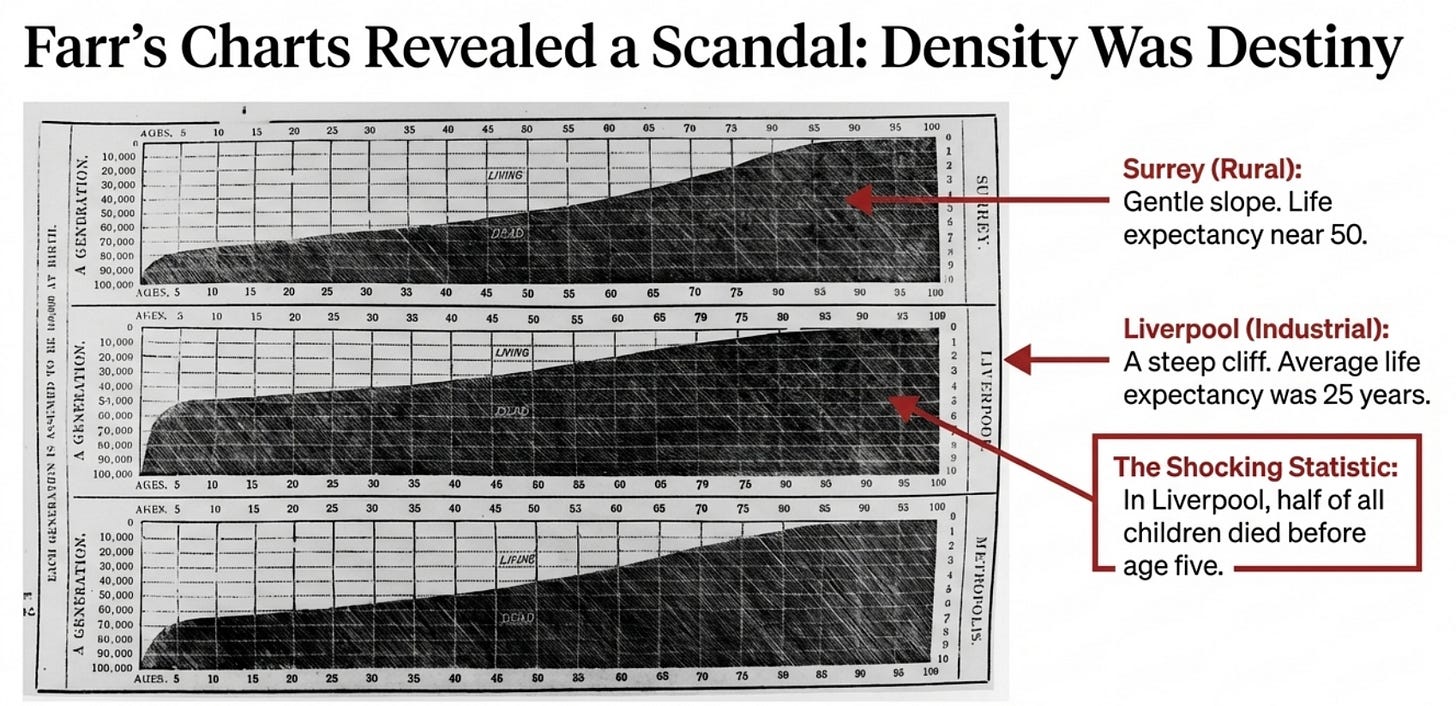

In the 1830s, William Farr, as the 'Compiler of Abstracts' at the UK's General Register Office, saw vital statistics as a tool for social reform. He began to map deaths with brutal clarity.

Data Became a Visual Argument

His driving question: Why were technologically advanced societies like Britain and the US seeing life expectancies decline in the first half of the 19th century? By looking at the data, Farr and his contemporaries realized that cities were not engines of growth; they were “mortality traps.”

Density amplified disease faster than trade amplified wealth. Wealth helped at the margins, but it couldn’t buy immunity from contaminated water. Farr's work provided the empirical argument that drove the first wave of public health and sanitation reforms.

Intelligence does not save lives at scale. Systems do.

Measurement allowed us to see where people were dying, which allowed us to intervene “upstream.” The early gains in longevity came not from the hospital bed, but from the sewer pipe.

Layer Two: The Network Narrative vs. The Lone Genius

We are addicted to the “lone genius” narrative. We are taught that Edward Jenner, the brilliant country doctor, observed milkmaids and “invented” vaccination in 1796.

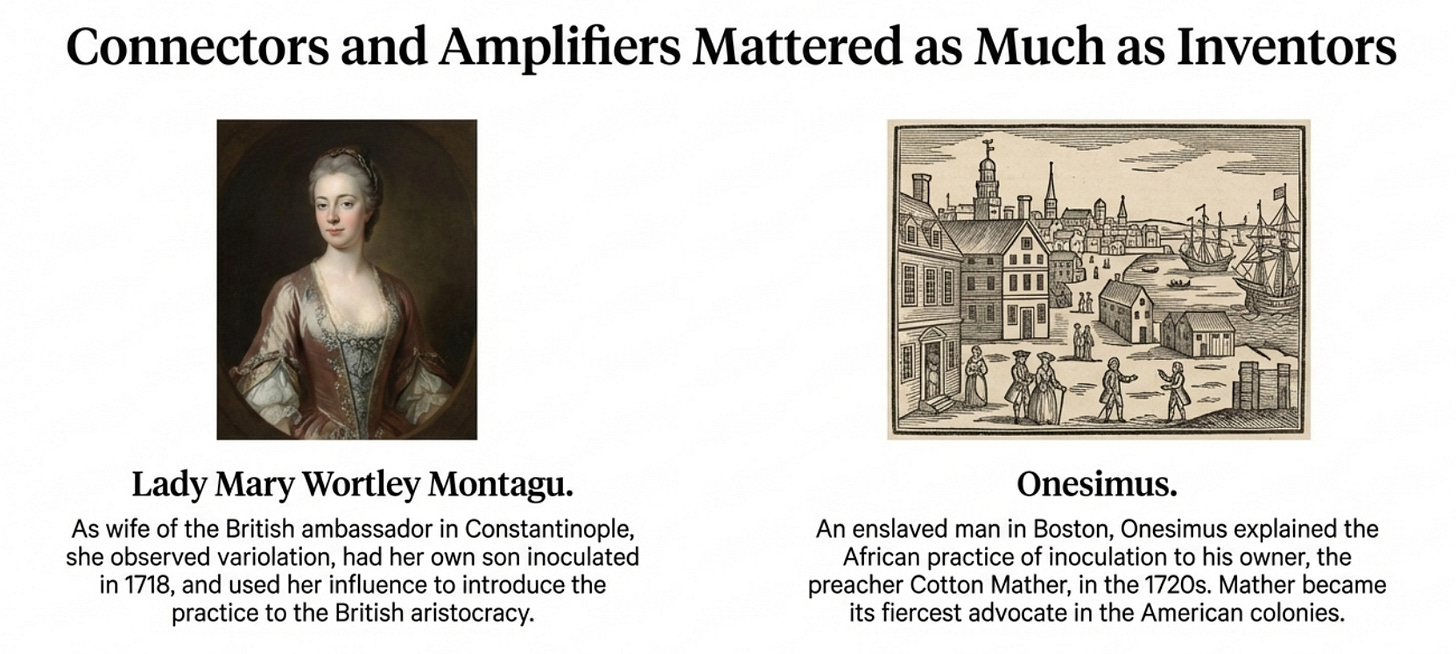

Jenner’s breakthrough was the culmination of ideas that had travelled across Asia, Africa, and the Ottoman world for centuries. Practices resembling inoculation were traditional in China and India long before they reached Europe. Lady Mary Wortley Montagu observed these practices in Turkey and brought them to London; an enslaved man named Onesimus introduced the concept to Cotton Mather in Boston.

Progress Is Not a Moment of Genius. It Moved Through Networks.

Layer Three: The Hierarchy of “Boring” Innovation

In our pursuit of progress, we suffer from a "prestige bias" that prioritizes cinematic breakthroughs over systemic reliability. We celebrate the intensive care unit and the experimental drug, yet the foundation of our "extra life" was built using far less glamorous materials: plumbing, spreadsheets, and refrigeration.

If we were to rank innovations by the sheer volume of lives saved—rather than their ability to capture headlines—the hierarchy of progress would look remarkably unromantic:

The Sewer and the Sink: For centuries, cities were “mortality traps” where density amplified disease faster than trade could generate wealth. The simple act of separating waste from living space through sewerage and providing clean drinking water broke the cycle of fecal-oral transmission that had decimated populations for millennia.

The Thermometer as Data Point: Data made the invisible visible, allowing societies to intervene “upstream” before diseases reached the hospital.

Pasteurization and Food Safety: We often forget that food was once a primary vector for lethal pathogens. The “boring” regulation of milk and the stabilization of food supplies through nutrition science and fertilizers essentially neutralized environmental risks that were once a standard part of the human condition.

Primary Care vs. Tertiary Glory: A fundamental truth of public health is that the most significant declines in mortality occurred before the arrival of modern "miracle" drugs. The heavy lifting was done by the "invisible" spread of primary health: basic sanitation, cleaner environments, and reduced exposure. Deaths from tuberculosis and diarrheal diseases fell decades before effective pharmaceutical therapies existed

The Latecomers to the Revolution

In September 1928, Alexander Fleming returned from a two-week vacation to find a petri dish of Staphylococcus contaminated by blue-green mold. Before discarding it, he noticed a clear zone where bacteria had been destroyed. The mold, he realized, was releasing a substance that lysed bacterial cells. Fleming named it penicillin—a chance observation that became medicine’s first true antibiotic. Seventeen years later, its impact earned him the Nobel Prize.

Soon, Antibiotics served as a powerful secondary layer of the shield, transforming once-lethal bacterial infections into manageable conditions after the preventive layers had already stabilized the population.

The Indian Miracle and the Fertility Paradox

India’s experience provides the clearest modern data set for this transformation. At Independence, India’s life expectancy was barely 32 years. Open defecation was widespread. Clean drinking water was scarce. Infectious disease dominated the burden of death. Today, it is nearly 70.

This rise was not driven by tertiary hospitals. The Green Revolution stabilised calories. The Expanded Programme on Immunisation reduced child mortality. Oral rehydration therapy turned diarrhoea from a killer into a manageable illness. Family planning and female education accelerated the fertility transition.

Now, the most striking second-order (could be) effect is the “fertility collapse.”

India’s birth rates is going down not only because families getting wealthy, but may be due to children stopped dying. When survival becomes predictable, fertility adjusts downward. Population growth slows not through coercion, but through confidence. This is a universal demographic pattern: the “extra life” leads to a smaller, more stable population over time.

So, what next?

Because we are built to react to overnight tragedies, we have become blind to the long-term miracle we are living in. To truly appreciate this gift, we must first understand the quiet, persistent, and often difficult mechanics of how it was earned.

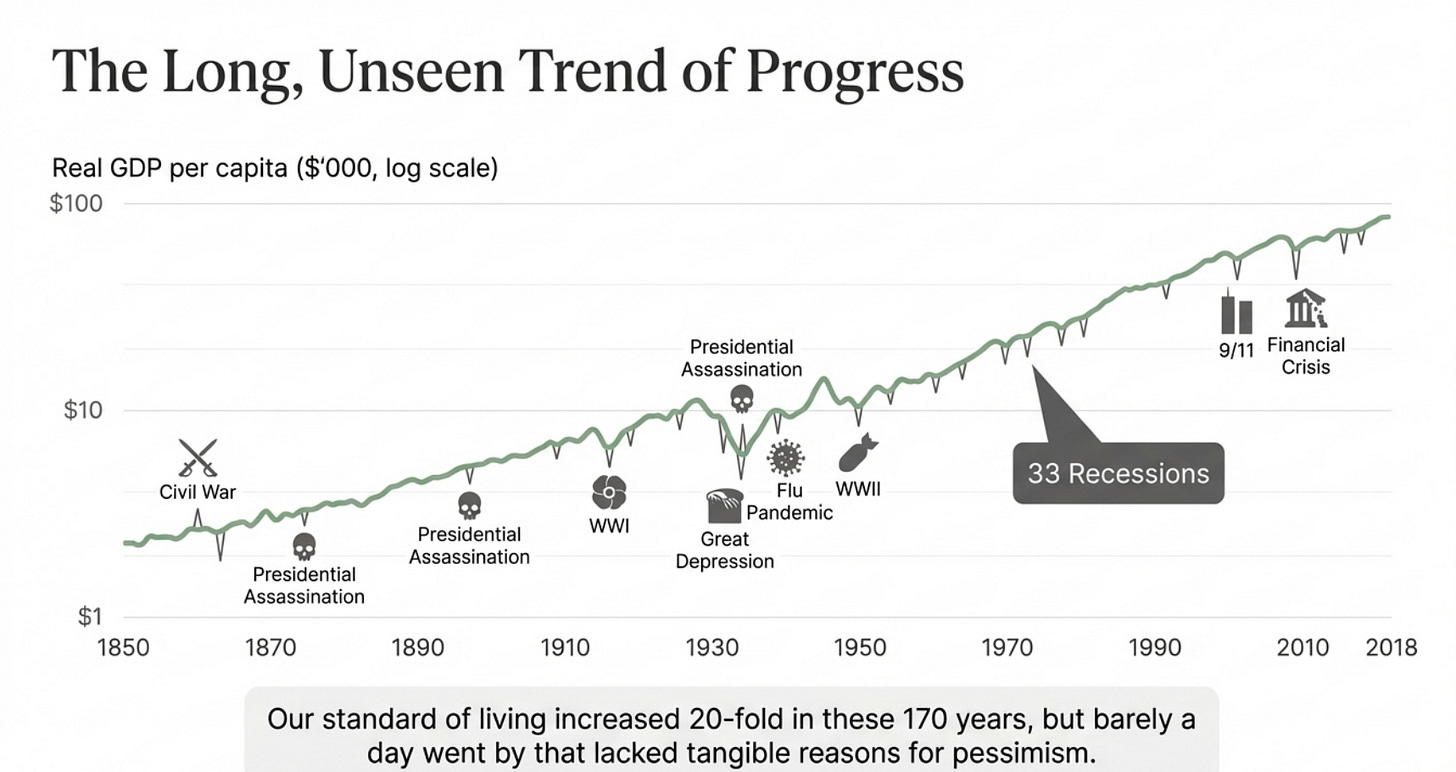

Despite our political dysfunctions and environmental challenges, we are living in a better world by the most fundamental metric possible: lives lived fully rather than cut short. This is true for economic fronts also.

We have been given an “extra life.” The challenge of the next century is ensuring we don’t let the shield break. The shield is not guaranteed to persist. It is an engineered marvel that requires constant maintenance. We must remember that our greatest achievement was not becoming immortal, but ensuring that we actually get the chance to grow old.

Don’t let the story of how we got here fade into the background

Progress did not make us immortal. It made us normal. And that may be the most extraordinary achievement of all.

Excellent review of evolutionary happenings

A good essay, poem or book must either be a product of deep thought or should provoke thoughts in the reader. This article does both. What it lacks (a very miniscule bit) in seamless journey between different fact milestones, it more than makes up in raising quite a handful of very relevant questions. The lack that I mentioned is not only understandable, but also admissible and forgiveable because of the eclectic nature of the topic. This is a highly recommended read to thoughtful readers.