The Slope Framework

The Fallacy of the Intercept: Why the Future Belongs to the Slope-Builders

Two decades ago, during my MBA days, I read Good to Great by Jim Collins. Like many of other B-schoolers, I felt electrified. The book offered a seductive, crystalline clarity:

disciplined people, disciplined thought, disciplined action.

Follow the framework. Find your “Hedgehog Concept,” and greatness would follow with the inevitability of a physical law.

But as the years passed, the excitement grew into a quiet discomfort. The 11 "Good-to-Great" Companies were:

Abbott Laboratories, Circuit City (Later declared bankruptcy in 2008), Fannie Mae, Gillette, Kimberly-Clark, Kroger, Nucor, Philip Morris, Pitney Bowes, Walgreens & Wells FargoCircuit City, Fannie Mae, Pitney Bowes—didn’t all remain great. Other stagnated and underperformed the index. One 3 can be still be considered as Gold-level (Abbott Laboratories, Kroger & Nucor)

It seems the book was less a map to future winners and more a sophisticated exercise in confirmation bias. It was a study of survivors, not a manual for creation.

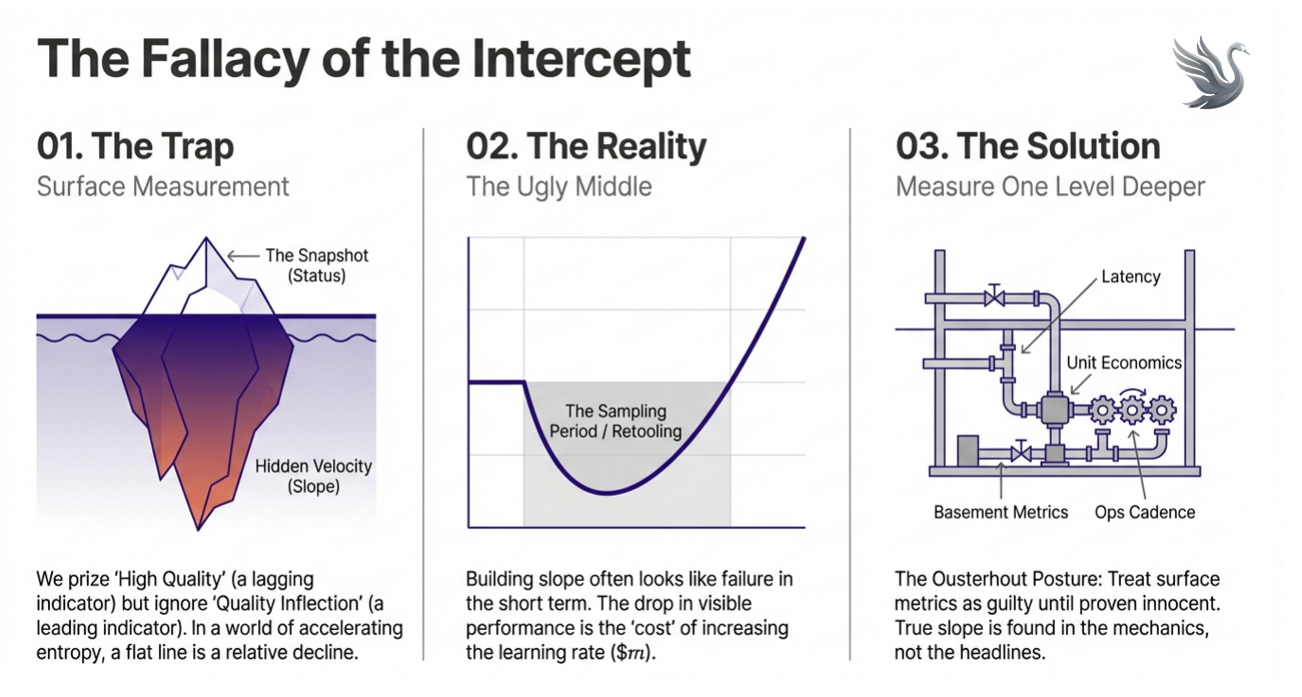

Greatness, it turns out, is far noisier, more path-dependent, and less reproducible than retrospective frameworks suggest. We have been taught to worship the “Intercept”—the point on the Y-axis where a company or a person sits today. We prize the “High Quality” label as if it were a permanent genetic trait. But in a world of accelerating entropy, the Intercept is a lagging indicator. It tells you where someone has been.

If you want to find the true “Learning Compounders” before the market rerates them, you must stop looking at the Intercept and start measuring the Slope: the rate of change that exists one level deeper than the reported reality.

The Ousterhout Posture: One Level Deeper

In his seminal paper, Always Measure One Level Deeper, computer scientist John Ousterhout (btw his video is the reason why i am writing this) argues that most system performance metrics are closer to marketing than truth. Engineers tend to measure what’s visible—average latency, total throughput—and if those numbers look strong, inquiry stops.

Ousterhout pushes the opposite posture: treat surface metrics as “guilty until proven innocent.” He recounts building a log-structured file system where his team believed data locality would improve performance. It was intuitive—a classic best practice. But when they measured one layer deeper, the result flipped. Locality actually worsened performance due to hidden garbage-collection dynamics. By interrogating the mechanics beneath the headline metric, they uncovered an insight others had missed.

The “Ugly Middle”: The Window of Opportunity

Ousterhout notes that when you first measure a system deeply, the results are often “riddled with contradictions and things we don’t understand.” In investing and leadership, this is the Ugly Middle.

This is the J-Curve trap. You will see companies where margins are dipping, depreciation is spiking, and employee costs are rising. To the Surface Measurer, this is a “Sell.” The Intercept is dropping.

But if you measure one level deeper, you see that the “Ugly” costs are actually investments in the Slope. The company is hiring CXOs from global majors (the “MNC Migration”), upgrading its tech stack, and obtaining global compliance certifications. They are “sweating” the organization to prepare for the next leg of growth. The market prices the pain of the Intercept. You buy the trajectory of the Slope.

This applies to personal growth as well. When you decide to learn a new discipline or pivot your career, your “Intercept” (your current status/income) often drops. You enter the Ugly Middle. People who worship the Intercept will call this a mistake. But if your learning velocity is high, your Slope has just steepened. You are building “Range,” and as the NYT study suggests, that range will eventually provide a level of greatness that a specialist can never reach.

Equity markets and organizational cultures behave the same way. Most investors and managers are surface measurers. They screen for high ROCE, low leverage, and steady growth. They are looking for “Greatness” as a finished product. But by the time a company has “arrived,” the Slope has often already begun to flatten. The most profitable investments—and the most resilient careers—are found by measuring the velocity of what is becoming better tomorrow.

The Polymathic Slope: Range Over Specialization

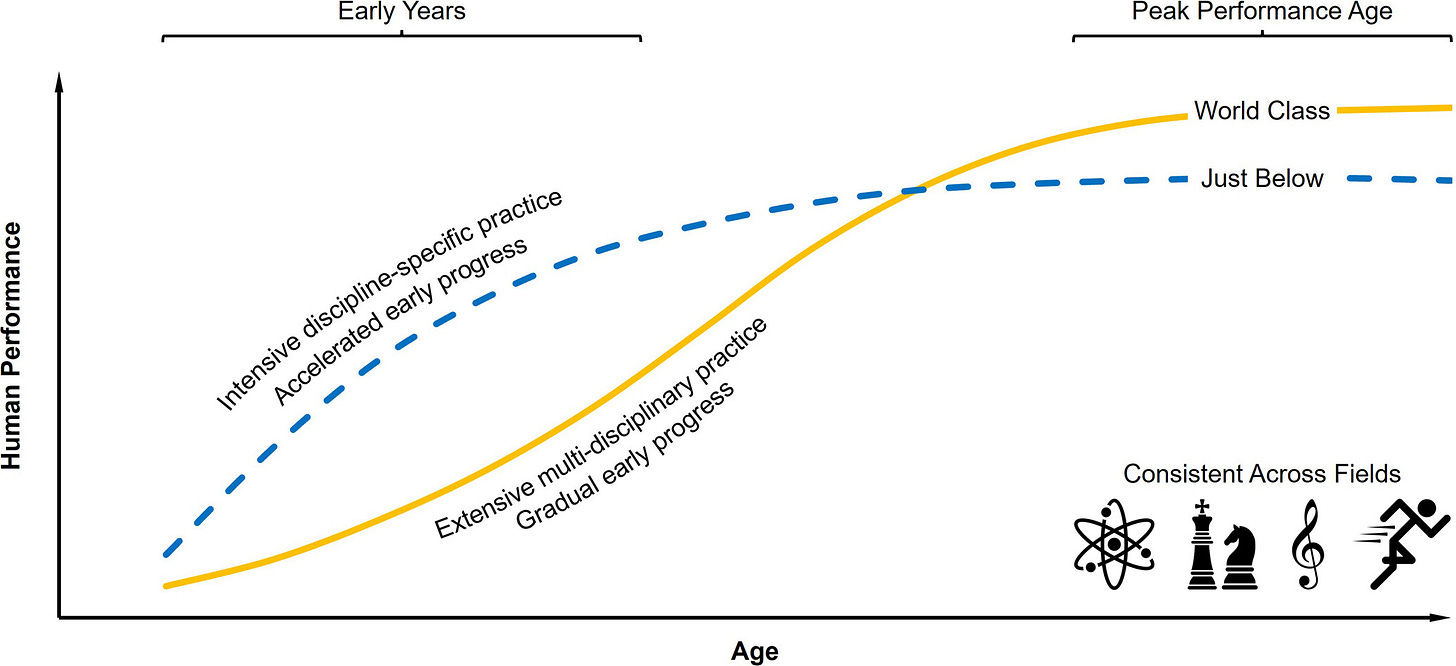

We often assume that a steep Slope requires hyper-specialization—the “Hedgehog Concept” of doing one thing better than anyone else. However, recent longitudinal studies suggest that this might be another Intercept trap. The study in the journal Science reveals a counter-intuitive truth: those who eventually reach the highest peaks of performance often start with a “sampling period.”

They engage in multiple disciplines early on, appearing behind their specialized peers (the Intercept), but eventually developing a much steeper trajectory (the Slope).

This “Range” provides both a psychological and operational buffer. When a company or an individual operates as a “polymath”—integrating technology, operations, and psychology—they aren’t just good at a specific task; they are good at the meta-skill of learning. As Steven Johnson (my favorite author on Innovation Framework) will say

“We take the ideas we’ve inherited or that we’ve stumbled across, and we jigger them together into some new shape.”

In the corporate world, this manifests as Strategic Range. A company that only knows how to do one thing may have a high Intercept today, but it is inherently fragile—one disruption away from obsolescence. The “Slope-builder,” however, is the organization that treats every new challenge as a cross-disciplinary experiment. Google has proven this again and again, successfully pivoting its massive talent pool into entirely new domains by relying on first principles rather than legacy playbooks.

Such entities don’t just hire for “Experience” (the Intercept); they hire for Aptitude (the Slope). As Ousterhout observes, when you hire for experience, you are often hiring someone who has already hit their limit—someone whose “line” has already flattened. When you hire for aptitude, you are betting on a fast learner who will eventually outpace the veteran because their trajectory is steeper.

I have personally been a beneficiary of this reality. Coming into the industry without a traditional “pedigree,” I didn’t have the luxury of a high Y-intercept. I started further down the axis.

The Fallacy of the Spike: The Compound of a Thousand Decisions

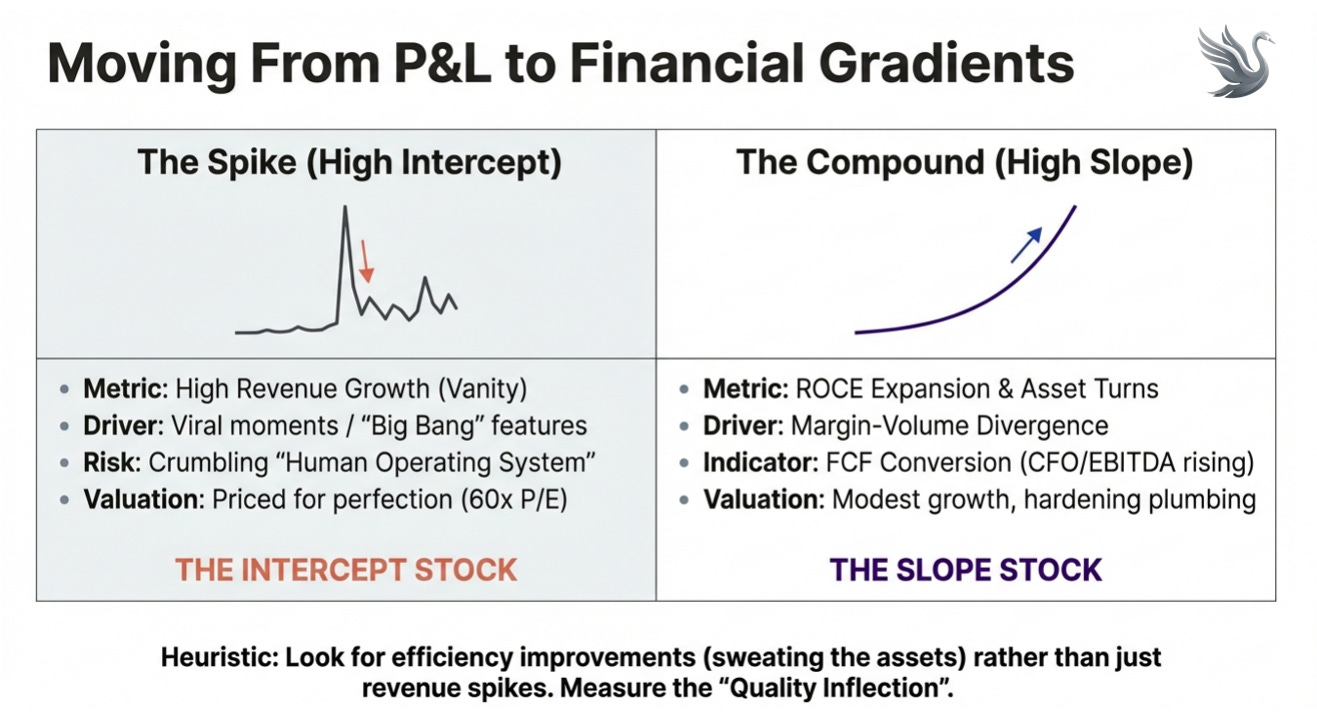

In the startup world, there is an obsession with the “Spike.” Founders chase the viral moment, the brilliant pivot, or the “Big Bang” feature that will catapult them to unicorn status. They look for the vertical line.

But greatness isn’t found in the spike; it’s found in the compound. Most enduring companies grow not because of one brilliant epiphany, but because of a thousand small, disciplined decisions that compound over time. The “Spike” is a temporary anomaly in the Intercept. The “Compound” is the manifestation of the Slope.

When we build for the spike, we sacrifice the plumbing. We ignore the internal dynamics that Ousterhout warns about. A “Spike” company might show 100% revenue growth, but if you measure one level deeper, you find a crumbling “Human Operating System” and negative unit economics.

A “Slope” company, conversely, might look boring. Its growth might be a steady 25%. But beneath the surface, the “Learning Compound” is at work. They are refining their collection cycles by 1% every quarter. They are improving their code base efficiency by 2% every month. They are institutionalizing the “Owner-Mindset” through ESOPs and incentive architecture. These are the “Small Decisions” that create a trajectory that eventually makes any “Spike” look like a footnote.

The Financial Gradient: Measuring Beneath the P&L

So, the key idea for you as an investor is

Don’t get too focused by static snapshots of excellence. True alpha is found by measuring the velocity of a company's improvement.

And, to find these companies in the public markets, you must move from the P&L to the Financial Gradient. If the Intercept is “High Quality,” the Slope is “Quality Inflection.”

The ROCE Expansion Gradient: A 30% ROCE is a beautiful Intercept, but it is usually priced at 60x P/E. There is no room for error. A “Slope” play is a company whose ROCE is 14% but has been rising 200 basis points every year for three years. Look at Asset Turns specifically. If the promoter is learning to sweat the same machinery for more revenue, the “Slope” is steepening regardless of what the bottom line says today.

The Margin-Volume Divergence: Measure one level deeper than Revenue. If Gross Margins are expanding while volumes are steady, and there is no raw material tailwind, you aren’t just seeing “profit.” You are seeing a Product Mix Shift. The company is moving from a commodity-taker to a value-maker. They are learning how to command premium pricing—a core “Slope” indicator.

FCF Conversion Maturity: Screen for the ratio of CFO to EBITDA. When this ratio starts rising, it’s a signal that the internal plumbing—working capital, collection cycles, inventory management—is hardening. This is the “Institutionalization Slope.”

The Algebraic Truth of Compounding

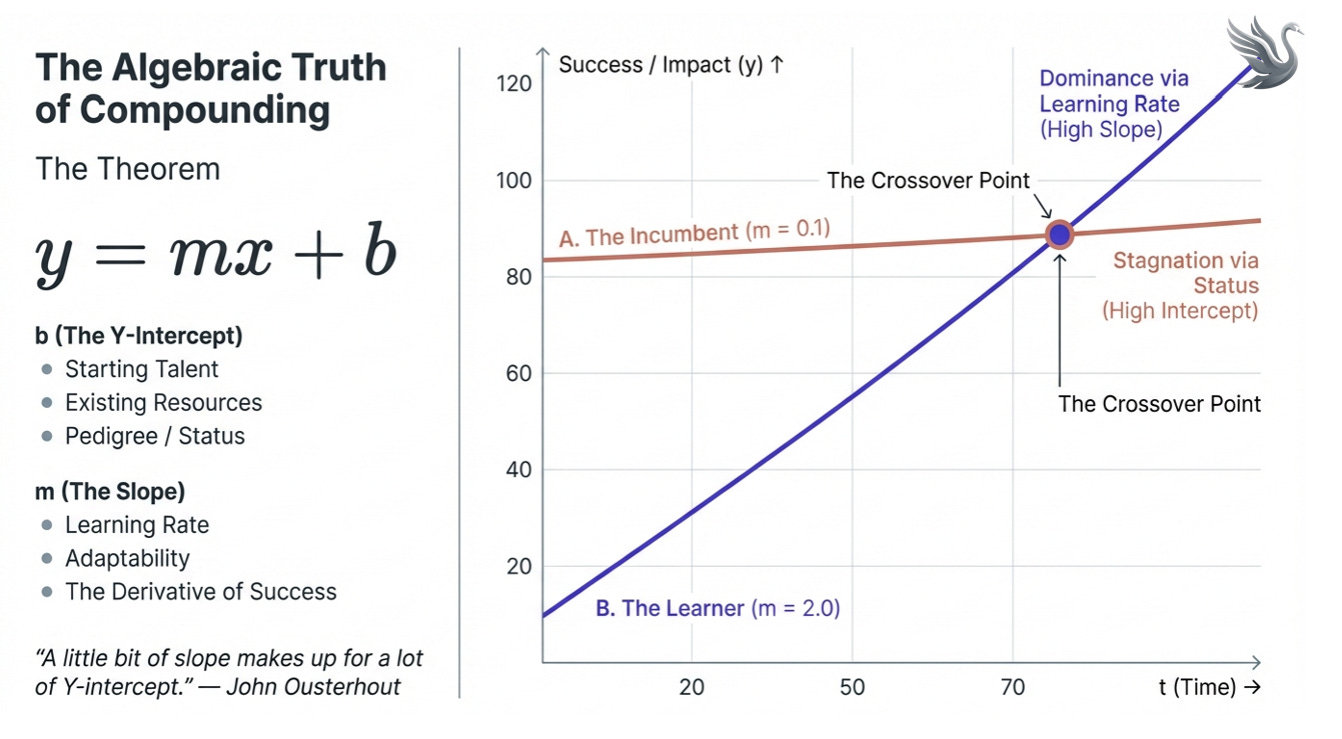

As Ousterhout often tells his students, “A little bit of slope makes up for a lot of Y-intercept.”

This is an algebraic certainty. If you have two lines, the one with the steeper slope will always eventually overtake the one with the higher intercept. In life, and in equities, we are often blinded by the Y-intercept—the prestige, the history, the current “quality.”

The Intercept Stock (or person) is the legacy blue-chip that has done the same thing for 20 years. It is “safe,” but its slope has flattened. It is a “Fixed Mindset” organization.

The Slope Stock (or person) is the “dumb” newcomer that everyone is underestimating. They might start behind, they might lack the “prestige” of the incumbent, and they might even be in the “Ugly Middle” of a sampling period. But because they have a Growth Mindset and are making those thousand small, compounding decisions, they are learning one or two new things every day.

Don’t be afraid of the company—or the individual—that “doesn’t know anything” about a new segment today. If their slope is high, they will catch up faster than you think. Most people get stuck in the “Fixed Mindset” trap—believing that greatness is innate and static. It isn’t. “Greatness” as defined by Jim Collins is a snapshot of a moment in time. True greatness is the derivative of that snapshot—the velocity of improvement.

Conclusion: Slope always wins

I think “Good to Great” framework didn’t fail because its principles were wrong; it failed because it treated a snapshot as a destiny. It looked at the Intercept, and assumed the foundation was permanent.

But the real world is governed by the Slope.

The most resilient entities—whether they are companies like Google or individuals like those of us who started without a pedigree—share a specific “Polymath Advantage.” They don’t just specialize; they integrate. They connect technology, operations, and psychology into a cohesive whole. They aren’t just “good at a task”; they are masters of the meta-skill: Learning Velocity.

In the long run, you don’t need heroics. You don’t need the perfect Hedgehog Concept or the once-in-a-century pivot. You just need a slightly steeper line. A little bit of slope, maintained over time, with “many small decisions” will build a foundation for the compound, rather than the temporary spike of the hero.

In the race between the “Prestigious Static” and the “Hungry Dynamic,” the math is clear: Slope always wins.

Ousterhout's Rule: If the slope is high, the catch-up is inevitable. Don't worry about the domain gap.

“Originality is the art of hiding your sources.”- Maria Popova.

But, I will not do that, and will lead you to the original source.

Here is the video that created the chemical reactions for this post!